Jordan Taylor/Staff Photographer

Ron Foreman portrays Delbert in “The Exonerated” on Tuesday Oct 17, 2017 in Titmus Theater. The Exonerated, is a play that focuses on the injustices in the criminal justice system including race, class, and gender.

Riki Dows | Correspondent

University Theatre’s Open Door Series presented “The Exonerated,” with showings that ran throughout NC State’s Diversity Education Week.

Based on true stories, the one-act play followed six wrongfully-convicted death row inmates as they told the audience their stories, including the circumstances that led up to their arrests, the misconduct of the criminal justice system, the cruel conditions of prison and death row and life after their exoneration.

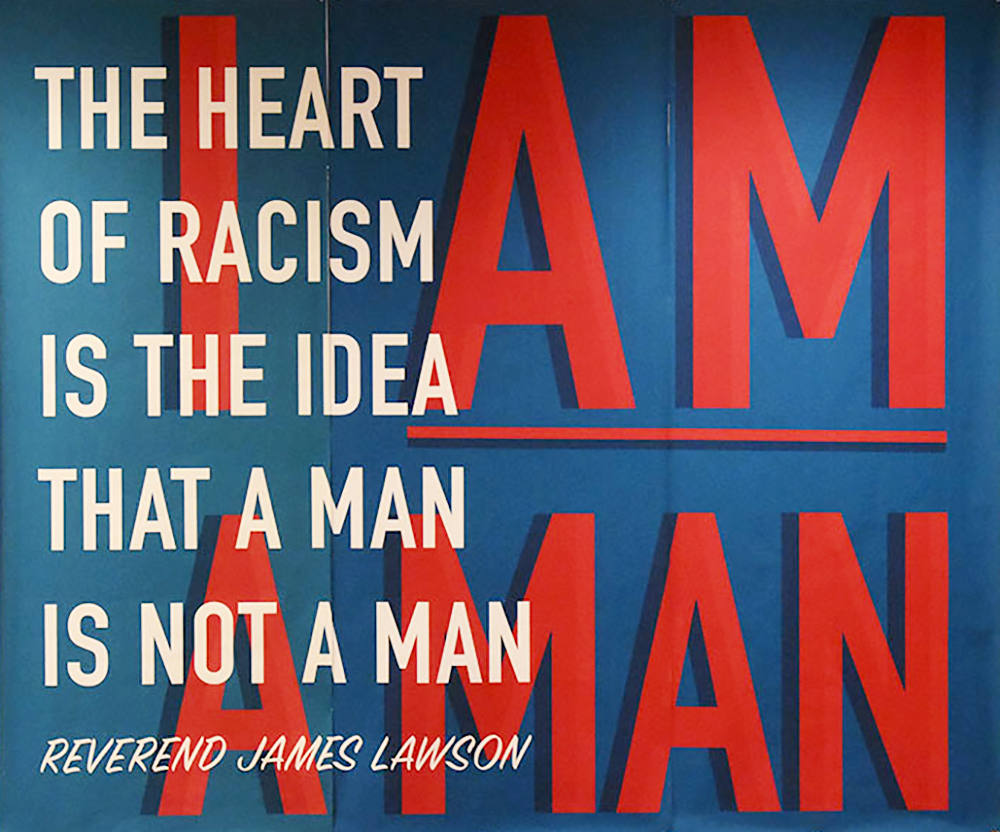

One of the exonerees was Delbert Tibbs, played by Ron Foreman. Tibbs was convicted of rape and murder even though local police had already determined he had an alibi. Still, the judge issued a warrant for his arrest and he spent three years on death row before being exonerated for mistaken witness identification.

In reflecting on the injustice of his case, Tibbs says, “As I sometimes tell people, if you’re accused of a sex crime in the South, and you’re black, you probably shoulda done it, you know. Because you’re gonna be guilty.”

Robert Earl Hayes was played by Jeremy Wesonga. Hayes was also accused of raping and murdering a white woman in 1990, and knew that he was going to prison because there were “eleven whites and one black on (his) jury.”

Hayes’ wife, Georgia, portrayed by Skylar Skinner, implores the audience with this question: “And do you think, seriously… if the roles had been reversed, if it had been a black woman and a white man, it would’a been like that?”

When I heard this line, my mind immediately went to the number of cases where we’ve seen this double standard play out in America’s criminal justice systems. I thought about Dylann Roof, who was allowed a calm arrest, complete with bullet-proof vest as per his basic civil rights, in comparison to police brutality victims like Eric Garner, forcefully brought down in a severe chokehold that crushed his windpipe and eventually killed him.

I thought about Brock Turner and how he was only sentenced to six months in prison, and was out in three, for the rape of an unconscious victim versus the 15-year sentence Cory Batey received for the exact same crime.

Hayes’ line is a perfect reflection of the way we see law enforcement use race as a deciding factor in how they treat suspects of a crime today.

On the opposite side of the spectrum, we have Sunny Jacobs. Jacobs’ story was unique in that the veil of discrimination did not color her conviction the way it had for the other inmates. She was white woman, and still, the system failed her when a perjured witness condemned Jacobs, along with her husband Jesse, for the deaths of two police officers in 1976.

Jacobs, as portrayed by Natalie Sherwood, gave a monologue about the degradation of these “correctional facilities.”

“They take your clothes, they give you a number, so basically they’re taking who you are from you. You no longer have a name, you’re a number, you’re locked inside this tomb.”

Pondering the words of her character, Sherwood wondered, “Where is the ‘correction’ in that…How do we expect these people to re-embrace our guidelines when they have been suffering from our ‘moral’ punishments for years on end?”

Jacobs’ story is the perfect testimony to why we all should care about the failings of the criminal justice system and the implications of the death penalty. Wrongful conviction is not just a problem for people of color. It isn’t restricted to only people that have done wrong. Sunny Jacobs was a white woman who was in the wrong place in the wrong time. It can happen to anybody.

When asked about why being a part of this production was important to her, Sherwood said, “(It) addresses the infinite complications within our justice system; how it is elitist, how it lacks a checks and balances system to ensure compliance with ethical practices, how it disadvantages those of lower socioeconomic status and those belonging to minority groups often vilified in this country, how it prioritizes finality above truth and its namesake of justice.”

The audience was floored by the commitment of the students to portraying such a controversial and emotionally-packed plotline.

“It was super chilling and captivating,” Molly Riddick, a senior studying political science and theatre arts studies, said, “I don’t think I got an emotional break from the entire run of the show.”

In addition, the audience really appreciated the story’s ability to make the audience think about current social issues.

Rachel Walter, a senior studying biological sciences and Spanish, backed this up by saying, “It’s shocking to realize that their stories are not the work of fiction, but are the result of a broken system that far too few people are aware of…it prompted me to remove the rose-colored glasses I so often wear to critically reflect on and examine the state of our judicial system and nation as a whole.”

I was also impressed by the actors’ willingness to take their performances to the extreme. The material required some actors to say racial slurs and express discriminatory mindsets that they would never say outside of acting. Their commitment to telling the story made the image more vivid, which really increased my emotional reaction to the stories.

Overall, I think this show was an amazing way to start a conversation that not a lot of students knew we needed to have. The retelling of the exonerees’ stories informed the audience of an epidemic that has been improved by the innovation of DNA evidence and organizations like the North Carolina Center on Actual Innocence but is still happening to people, especially people of color, today.