Photo Illustration by Glenn Wagstaff

Kennysha Woods | Staff Writer

There are some common struggles among the students of the Wolfpack; we’re all trying to balance classes, clubs, jobs, and social lives—all while desperately trying to get a full eight hours of sleep when we can. But a recent survey conducted at NC State shows that for some students, homelessness and food insecurity are also part of their struggles.

In October 2017, a survey was emailed to 7,000 randomly selected students, asking questions about their experiences with homelessness and access to food. Dr. Mary Haskett, a professor of psychology and member of the Steering Committee for the Food and Housing Security Among NC State Students Initiative, worked with two undergraduate research assistants to conduct the survey. These students are also members of the Steering Committee—Shivani Surati, a second-year student studying health sciences, and Indira Gutierrez, a third-year student studying psychology.

“I knew we had students on our campus who were struggling with not enough food and with really vulnerable living arrangements and homelessness,” Dr. Haskett said. “I really wanted to try to bring people together to solve this problem, and the first thing we decided we needed to do was to understand the extent of this problem.”

The survey consisted of 35 questions and the questions were divided into topics such as food and nutrition, sleep and housing, methods of paying for college, and economic experiences.

“I think each category can tell us about what aspects of food and housing insecurity are most common among college students and the adverse effects it can have on academic performance,” Surati said.

This is the first study of its kind to be done on NC State students, and the questions were adapted from similar surveys of different universities in the country.

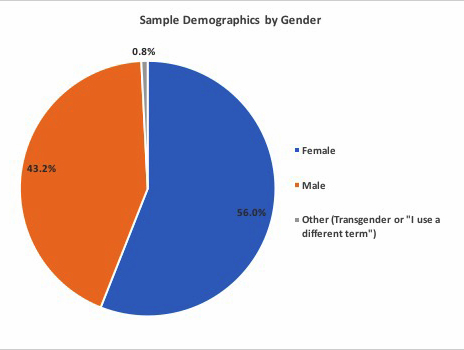

This pie chart compares the demographic breakdown, by gender, of students who completed the survey. Graph composed using study data.

Major Findings

Of the 1,949 students who replied, 14% had experienced low or very low food security in the past 30 days, while 9.6% had experienced homelessness in the past 12 months. The survey indicates that food and housing insecurity are closely related, with 24% of students who experienced homelessness in the past year also experiencing food insecurity in the past 30 days.

“In terms of how we compare to other campuses,” Dr. Haskett said, “our rates of food insecurity tend to be consistent with what other universities are reporting, and maybe even lower than a lot of other universities. But our rates of homelessness are stunning.”

The survey report cites the Youth Risk Behavior Survey of 2015, which found that 4.5% of high school students in NC had experienced homelessness during the prior year.

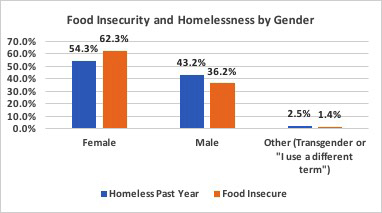

This graph compares the percent, by gender, of students who completed the survey and experience food insecurity or homelessness. Graph composed using study data.

Food and Housing Insecurity: From the Pack

Gutierrez shared her personal experience with food and housing insecurity: “This summer was the first time that I had the most serious concerns about housing. My mom has a chronic illness, and the rent increase was so significant she could no longer work long enough hours to afford it and maintain her health.”

After having to pay the fee out-of-pocket to keep her things in Wolf Village, Gutierrez stayed with one of her brothers of Mu Beta Psi and worried about how she was going to be able to buy healthy meals.

“School meal plans cover food, sure, but choosing the cheapest meal plan comes at a cost,” Gutierrez said.

Another student, Qulea Anderson, a second-year student studying creative writing, shared her experience of housing insecurity this past Christmas break: “When finals were coming up and I was planning on how I was getting home, I was communicating with my cousin to see when she would be able to come and get me. Later on in the week I found out that I wouldn’t be able to stay with her for Christmas break due to her own reasoning. With that I had to scramble to figure out what I was going to do. I knew that it wouldn’t be wise for me to stay on campus cause I wouldn’t be able to provide for myself food-wise. I ended up telling my best friend about what was going on and she invited me to stay with her for break.”

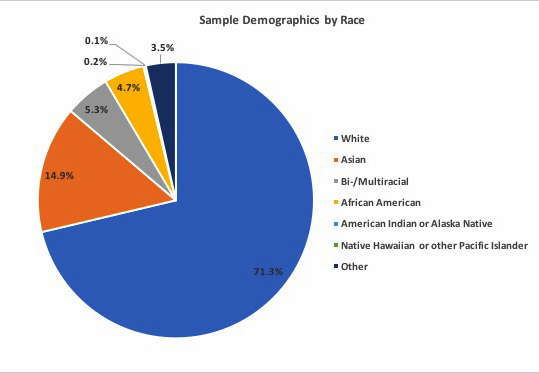

This pie chart compares the demographic breakdown, by race, of students who completed the survey. Graph composed using study data.

What are the Causes?

There are a combination of factors leading to homelessness and food insecurity among college students. According to the report, these factors include the rise in the cost of living for college students, the increased tuition costs outpacing increases in financial aid, stagnant minimum wage and less availability of affordable housing.

But despite these setbacks, the survey indicates that many of these students work part-time and full-time jobs to sustain their living; in fact, students who had experienced food and/or housing insecurity were more likely to be working or looking for work. The report highlights that 37% of food insecure students were working more than 20 hours a week.

Sarah Wright, an academic coach of Student Support Services (SSS), Pack Promise Coordinator, and member of the Steering Committee, works with a small population of 250 under-resourced students.

“To see the results of the a campus wide survey, especially with the [homelessness rate] being so high, that was shocking to me,” Wright said. “I hope it’s shocking to other people, and I hope they act upon using that number as a motivator to do something about it.”

Dr. Haskett said, “These are not students that we could dismiss by saying, ‘Well they just need to get a job. I worked when I was a student and I lived off of Oodles of Noodles.’ These students are working hard. They’re employed at higher rates than the general population. They’re looking for work in addition to already working, holding more than one job. They’re doing everything right, but what they’re not doing, and what we as a university can help with, is taking advantage of the financial resources that they may be eligible for.”

Such resources include Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), TRIO programs, campus food pantries, meal donations and on-campus emergency housing.

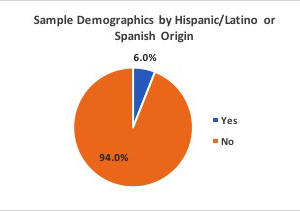

This pie chart compares the demographic breakdown, by Hispanic/Latino ethnicity, of students who completed the survey. Graph composed using study data.

Problems to Address

So what keeps these students from accessing these resources? One major problem is the lack of awareness of financial assistance resources.

“We have a huge population of students who don’t know they’re eligible for SNAP benefits, which can equate to $160 a month for food,” Wright said. “So I think their awareness of their resources is important.”

For Gutierrez and Anderson, awareness of these resources proved useful. Anderson discovered Feed the Pack Pantry when she consulted her friends and TRIO about her situation. “When I brought it up with my roommate and my academic coach, that’s when I was told about the resources on campus,” Anderson said.

Gutierrez also benefited with the aid of TRIO; she “had a place to go for questions [she] had about resources in food, housing, and general how-to questions.”

However, Gutierrez added that “not everyone has TRIO as a resource since there are limited amount of spaces for TRIO.”

Another major problem is the stigmas surrounding people seeking help from these resources and having discussions about issues of food and housing insecurity.

“I do think students feel marginalized and they feel they aren’t part of the wider community of NC State’s campus because nobody talks about it,” said Dr. Haskett, “so nobody understands that there are lots of students struggling. It feels very isolating.

“One of the things that we’re trying to change on campus is that stigmatization. We want to have an open, transparent conversation about this so that it becomes a part of our conversation with students and among students to destigmatize asking for help.”

Anderson said, “People also associate being homeless with being dirty, dumb, and that the person deserves it. They think that the person did it to themselves and that they can get out of it as easily as they got into it… But people don’t want their pride to suffer and to be pitied. They might be scared about being harassed or just feel like people won’t actually help them even if they speak out. Nobody wants the whole world to know that they can’t provide for themselves so why even discuss it?”

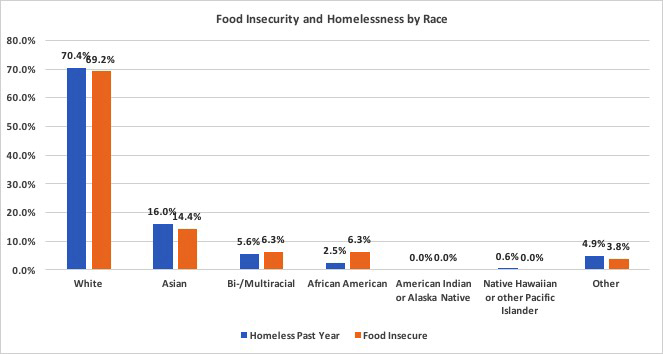

This graph compares the percent, by race, of students who completed the survey and experience food insecurity or homelessness. Graph composed using study data.

What Can NC State Do?

The report suggests possible solutions to lower NC State’s rates of homelessness and food insecurity. These solutions include establishing a single point of contact to provide struggling students with quick and efficient help in accessing assistance programs.

Wright said, “Reduce textbook cost, more open resource materials, but the biggest thing is there needs to be an office, person or group that is that single point of contact who is knowledgeable about the under-resourced population and managing students in crisis, and has relationships with community and campus resources to be able to get students the resources they need and work with them so that they can sustain staying secure.”

Other solutions include gaining more sources to fund programs helping these students and raising awareness of these issues and assistance programs among students, staff and faculty members to make them more knowledgeable of how to help struggling students.

But all of these solutions start from a common foundation—ending the stigma by fostering discussion of food and housing insecurity within NC State administration and among the student body. With more discussion, struggling students may be more encouraged to seek the available resources.

“I just want to see more workshops and discussions being centered around helping students with food and/or housing insecurity,” Anderson said. “There should be events that show students where they can go and who they can talk to. When they send out the howl emails and what not, they should have those events in there and even include links where they can go to a site or give them contacts that they can discuss in private if they don’t want their business to be public.”

Wright said, “Whatever the resource may be, it can’t be effective if the students who need it feel bad about going. That’s not necessarily a campus issues. It’s a societal issue.”

“Using resources available to you that satisfy your needs shouldn’t be a source of shame but an example of the resilience you have to get through an unfavorable situation,” Gutierrez said. “Hard times don’t discriminate… There’s no population in the world that is immune to crisis, things happen.”

The next step for the Initiative is to further investigate and analyze food and housing insecurity as it relates to mental health and well-being, first generation college students, international students, veterans, students with disabilities, students athletes, and parenting students.

All data will contribute to understanding these students’ situations, and will help NC State and Wake County enact solutions to help these students.

For more information on resources at NC State, please visit go.ncsu.edu/pack-essentials.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks