Qasima Wideman | Correspondent

Students at NC State are likely unaware that many of the metal products we encounter every day on campus- from the chairs we sit in, the desks we write on, to the door frames and trash cans in our buildings, were made by black and brown prisoners here in North Carolina who are paid next to nothing for their long hours of grueling labor.

WRAL reported that around 2,500 North Carolina prisoners were trained in 2014 to work in plants producing goods and performing services used in administration, packaging and distribution, printing, copying, sign production and reclamation. Their labor also includes woodworking, sewing, janitorial products, metal products, upholstery and reupholstery, optical products, laundry, meat processing, farming, canning, and food warehousing for Correctional Enterprises alone.

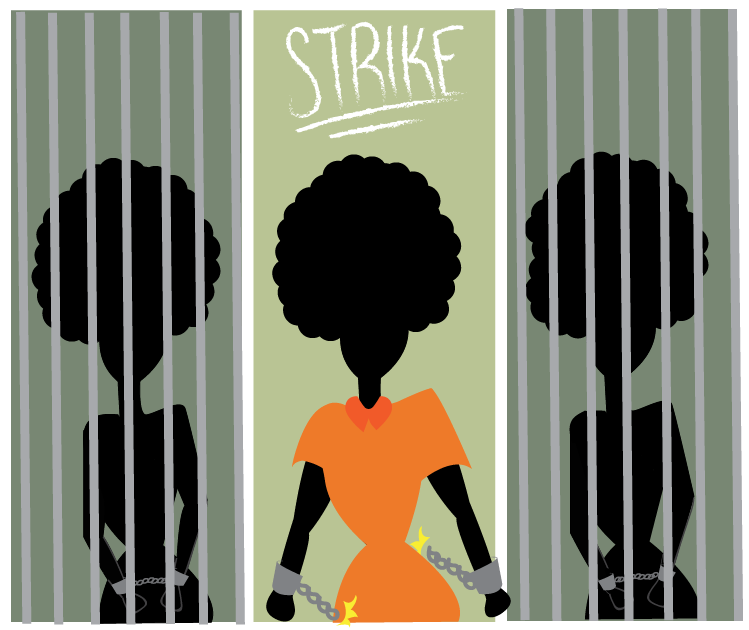

Correctional Enterprises is just one of numerous corporations that make millions in profits off of uncompensated prison labor in North Carolina, and that excludes that fact that prisoners also work within their own prisons making the food sold to them at prices they can’t afford, painting their own cells, to name a few of the tasks those in prison are forced to perform. That is why, come Sept. 9, these vital workers are going on a historic strike.

The metal goods on campus are produced by prisoners at the Brown Creek Correctional Institution’s metal plant in Anson County, North Carolina. It is public knowledge that these metal goods are then provided to tax-funded institutions within the state, from public grade schools, hospitals, courthouses, jails and prisons, to universities.

I interviewed Charles Cummings, a painting supervisor at Brown Creek, to confirm that NC State was a consumer of their products. “Yes,” he said, “NC State is one of our customers. We’ve done work for NC State several times. We have about 84 inmates at this time that we’re working here.”

Prisoners, however, are not simply an invisible workforce. According to WRAL, prisoner-workers, in the best of cases, make between 16 and 26 cents an hour. That’s only enough to afford a $1.21 fifteen minute phone call to a loved one after almost a full eight hours of labor; and prisoners in the Durham County jail aren’t even that lucky.

“It would cost them twenty five thousand dollars to hire someone to paint just one pod,” writes a prisoner in the Durham County Detention Center who wishes to remain anonymous, speaking about the cost to the Department of corrections were they to hire a free person to paint the walls of the jail, “and they have these black men doing it… for a tray of food at night that consists of beans and rice and bread.” Multiple detainees in the Durham County Jail report being compensated this way.

Another prisoner writes, “I’ve written to let you know what’s been going on in this Plantation of today: do you know that they are working these black brothers for a tray of food that consists of beans and rice and bread? Aramark has contracted the whole jail out, and instead of them hiring someone to work they have the black men in here working for an extra tray of food, beans, rice, bread almost every day–two shifts, kitchen, laundry, sanitation, stripping and waxing of floors, painting and cleaning up sewage water that is backing up into the jail. And the food is cold and half-cooked.”

Detainees in Durham County Jail are working long hours for cold, undercooked and unsanitary food. According to Bernard Creek, another prisoner in the Durham Jail, “Aramark, the jail’s food service provider triples the inmates’ hot tray price. The food that they prepare is frozen and in bulk. For example, a meal for a C.O. is $2. One single buffalo chicken sandwich [for a prisoner] is 3.99, no juice, no chips. The ridiculous thing about this is Aramark makes $500.00 in profit just from one day of hot tray sales.”

While some detainees work these long hours for meager meals, others work in the hopes of false promises being fulfilled. “I’ve been working for 31 days in the kitchen and was supposed to get 4 days taken off [my sentence],” writes Deontae Richardson, another detainee of the North Carolina Corrections Department, “and upon me asking for it I was told that I can’t get any. I asked for a copy regarding work detail policy and was told there is no policy… I basically work for free with the intentions of receiving days off my sentence, only to be told no I can’t get any. And it’s not in black and white but made up rules on what they think and who they think should get it. What happened to equal opportunity? I work so I deserve these days.”

Prisoners are not taking these human rights abuses in silence. “There was a day people were refusing to go into the kitchen, and they threatened to lock everybody back. The other threat is you’ll be removed from the pod. Those threats keep people in line,” wrote Vincent Paige, an activist and detainee in the jail. “They don’t want to cut days off of those people, because that’s money for them. The longer those people stay, the more money the county gets. The added bonus they get is they’re working in the work pod, and that’s 65 people for free labor. In my opinion, it’s the same thing they used to do in the Old South. Keep everyone in the field working, you keep all the money. 65 people running your jail, from laundry, to sanitation, to cooking your food—all the officers have to do is just sit there, pretty much.”

He is not the first to notice the continuation of plantation politics that plays out behind prison walls. The Thirteenth Amendment states quite notably, “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.”

Those who doubt the reality that incarceration has indeed replaced chattel slavery in the United States need look no further than the historic 1871 court ruling in Ruffin v. Commonwealth, which stated “For the time, during his term of service in the penitentiary, he is in a state of penal servitude to the State. He has, as a consequence of his crime, not only forfeited his liberty, but all his personal rights except those which the law in its humanity accords to him. He is for the time being a slave of the State. He is civiliter mortus; and his estate, if he has any, is administered like that of a dead man.”

Incarcerated people nationwide are planning a general strike on Sept. 9, the 45th anniversary of the Attica Uprising. According to the New York Times article Attica, Attica: The Story of the Legendary Prison Uprising, the 1971 uprising at Attica Prison in New York occurred after prisoners had been filing official complaints and requests for months on end to have their basic rights, including and especially fair pay, in addition to adequate access to toilet paper and reasonable religious freedom; to no avail.

They developed a formal list of demands and, on Sept. 9, 1971, were able to control over half of the prison and keep guards hostage with minimal violence in one of the most powerful and least celebrated civil rights protests in American history. On the Sept. 13, Governor Nelson Rockefeller oversaw one of the bloodiest crackdowns on political organizing to date in the U.S. State troopers gassed and opened fire on both detainees and guards trapped in a 50-by-50 yard space, killing 29 prisoners and ten guards.

Prisoners in North Carolina and throughout the country will celebrate the anniversary of the Attica uprising on September 9th by staging a labor strike in protest of prison slavery. “Think about the work pod,” writes one detainee in the Durham County Jail who is planning to strike on the 9th, “There’s a reason so many people get arrested for such minor infractions. It’s because the jail saves money. They arrest us and let us work in the work pod. Doesn’t cost them a dime. We need to stop working. Cost them money…. If the work pod united and struck then we would cost the jail THOUSANDS.”

This will not be the first major protest by prisoners in the Triangle area against abusive work conditions. The Women’s Prison on Bragg St, just a few miles up the road from Central Prison and NC State campus, was the site of another major prison labor strike in the 1970s.

The Bragg Street Women’s prison used to have an enormous laundry facility where incarcerated women were forced to do the laundry for all state employed workers’ uniforms, from hospital scrubs to police uniforms and orange jumpsuits, in extremely hazardous and unfair conditions.

In the wake of the acquittal of Joan Little, a black incarcerated woman who survived a sexual assault by a prison guard by stabbing her attacker with an ice pick, the women imprisoned on Bragg Street staged a strike and takeover of the yard that resulted in the laundry facility being permanently shut down and their demands about safety from predatory guards being heard.

Supporters on the outside are also organizing for prisoners. On September 9th at 7:30PM, people will gather at Durham Central Park at 501 Foster Street for a march in solidarity with striking prisoners.

They are keeping up regular correspondence with prisoners throughout the state and have formed an independent investigation team of community members including formerly incarcerated people to shine light on the human rights abuses in North Carolina’s prisons.

Students can support these efforts by writing letters and sending books to prisoners through various local and national organizations that support prisoners, like Prisonbooks NC, Black and Pink- which fosters correspondences and produces a free newspaper for incarcerated LGBTQ+ people, and the Inside-Outside Alliance, another local organization supporting prisoners.

We can also support striking prisoner-workers by demanding our university boycott prison labor, and stop purchasing products from the Brown Creek facility and any other plants enslaving incarcerated people.