Stephanie Tate | Managing Editor

Caught in between Martin Luther King Day and Black History Month lies the consistent appraisal of Martin Luther King Jr. Every year from his national holiday in January until the end of February, those who oppose policies that would align with Martin’s teachings resurrect his quotes to show that they do in fact believe in “equality.”

Martin is best known for a legacy of nonviolent peaceful protests that objected to the unjust treatment of African Americans in America. In the midst of painting Martin as the face of the Civil Rights Movement, we oftentimes leave out the voices and faces of others who contributed to the movement.

Malcolm Little, later known as Malcolm X, is one of those voices. The life and legacy of Malcolm X is scarcely taught in schools and when it is, Malcolm is illustrated as a violent antagonist to Martin. There is no denying that Malcolm and Martin were two very different men, however they had a similar goal: to obtain equal rights for African Americans.

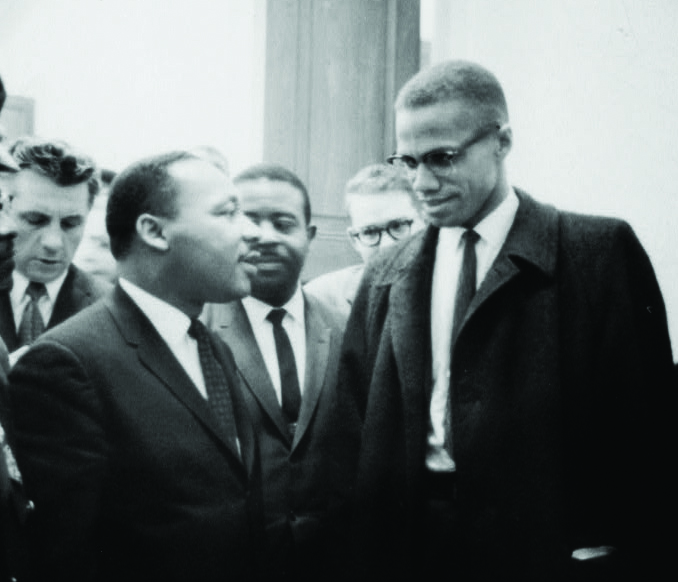

Despite their juxtaposed positions on how to achieve this goal, the two had much respect for another. With that said, respect never stood as enough reason for the two to see eye to eye.

In a 1963 interview with Malcolm X Dr. Kenneth Clark asked Malcolm “Well, Reverend Martin Luther King preaches a doctrine of non-violent insistence upon the rights of the American Negro. What is your attitude toward this philosophy?” In response, Malcolm X remarked that “The white man pays Reverend Martin Luther King, subsidizes Reverend Martin Luther King, so that Reverend Martin Luther King can continue to teach the Negroes to be defenseless.”

Remarks about Martin were not uncommon coming from Malcolm, which more than likely contributed to the idea that they were two opposite ends of a spectrum. Although Malcolm had gone on record calling Martin both a chicken wing and a fool, he also said “Dr. King wants the same thing I want–freedom!”

Towards the end of their lives, both seemed to become more moderate in their views. In his letter from Birmingham jail Martin acknowledges that the frustrations of black nationalists such as the Nation of Islam, were warranted. He refers to the black nationalists as one force and his model of peacefulness until integration as another force.

“I have tried to stand between these two forces, saying that we need emulate neither the “do nothingism” of the complacent nor the hatred and despair of the black nationalist,” said Dr. King. A letter from Malcolm, recovered by the Martin Luther King Paper Project, inviting Martin to speak at a Muslim rally read “A United Front involving all Negro factions, elements, and their leaders is absolutely necessary.”

According to PBS during his visit to Selma, Malcolm visited, Coretta Scott King, the wife of Dr. King to inform her that “I didn’t come to Selma to make his job difficult. I really did come thinking I could make it easier. If the white people realize what the alternative is, perhaps they will be more willing to hear Dr. King.”

After the death of Malcolm X in 1965 Martin apologetically sent a telegram to Betty Shabazz the wife of Malcolm. Part of the telegram read “While we did not always see eye to eye on methods to solve the race problem, I always had a deep affection for Malcolm and felt that he had the great ability to put his finger on the existence and root of the problem.”

While they disagreed on the methods to reach the destination, both Malcolm and Martin, kept freedom at the forefront of their movement. Malcolm X said in his autobiography “the goal has always been the same, with the approaches to it as different as mine and Dr. Martin Luther King’s non-violent marching, that dramatizes the brutality and the evil of the white man against defenseless blacks. In the racial climate of this country today, it is anybody’s guess which of the “extremes” in approach to the black man’s problems might personally meet a fatal catastrophe first — “non-violent” Dr. King, or so-called “violent” me.”

With both Martin and Malcolm being tragically assassinated at the age of thirty-nine, it would seem that they both met a fatal catastrophe. However, when looking at the activism on our campus, I can say that their movements have not met that fatal catastrophe. When looking at the amount of African American students committed to make our campus a more inclusive place I am lead to believe that regardless of whose path we take, we are slowly but surely approaching that end goal of freedom.